Flash Parker’s Basic Filter Guide

Version 1.0

Contents:

Part 1 – Graduated Neutral Density Filters

Part 2 – Circular Polarizers

Part 3 – Neutral Density Filters

Part 4 – Creative Filters

Part 5 – Stacking Filters for Dramatic Effect

This guide will serve as an introduction to those interested in learning how to use filters creatively and functionally. It will also serve as a place I can point people when they ask me “how did you do that?” after they simply ignore the information I upload with each and every photo. Clearly my GEEK section and the EXIF data are not getting the job done!

With that, let’s begin. I’ll be quoting and piggy-backing Thom Hogan here, a photographer I greatly respect and admire. We are entirely different shooters and have different views on things (he’s been doing this longer and is better than I am, so take that for what it’s worth!), so you should be able to learn a thing or two about using extra glass if this stuff is new to you.

The basics. I’m going to pilfer this directly from Hogan, because he’s right.

In general, filters can be used to:

- Increase or decrease contrast

- Change colors or color balance

- Change exposure (partially or fully)

- Add a visual effect (Hogan, 2003)

PART 1: GRADUATED NEUTRAL DENSITY FILTERS (GND)

I use filters to change exposure – partially – more often than I use them to change colours or colour balance. That’s why my kit is stocked full of Graduated Neutral Density (GND from here on out) filters in a variety of grades; 2, 4, 8 and 10+. I’ll get to each of them individually just as soon as I sort out some of this terminology.

A GND filter is useful for when you have difficult exposure levels in a scene. The most obvious examples is the sunset shot. Think back to your days using a point and shoot camera. You’re witness to a blood-red sky at sunset over, let us say for argument’s sake, the ocean. In that ocean is a boat. You want to make an image with an even exposure but when you click the shutter on your point and shoot then look at the LCD screen, what do you see? White. There is no sea of red. Only white. The sky is one big blown highlight and your picture sucks. Why?

Because your camera, to dumb it down, can’t deal with all the information you’re throwing at it. It can’t handle all that light in the top of the frame – the sun – and the more dimly lit boat and water at the same time. You need to fix that. You can fix that, now that you’re the proud owner of a DSLR (I’m assuming you are!). What you need is a GND (Graduated Neutral Density, remember?). A GND Filter, slapped in front of your lens, brings down the exposure level in one part of the scene (the top half, in our example) while leaving the other half intact. It does this by being dark and light at once.

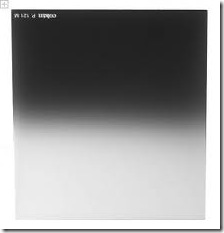

Above; a GND with a value of 8. The dark half of the frame stops twice as much light as a GND4. A GND4 stops twice as much light as a… oh, you get the idea. Going from light to dark, bottom to top, it’s easy to see how an image will be affected by this type of filtration.

In the image above, taken on Pangkor Island west of peninsular Malaysia, I was looking to retain a little detail in the watercraft while also keeping as much detail in the sun and the clouds as possible. This is no easy feat without filtration; shooting into the sun, even a setting one, creates myriad exposure problems for a camera – be it of the point-and-shoot, APS-C or Full Frame sensor variety. Therefore I used a HARD GND8 to bring down the light in the sky and fired away.

In the image above, taken on Pangkor Island west of peninsular Malaysia, I was looking to retain a little detail in the watercraft while also keeping as much detail in the sun and the clouds as possible. This is no easy feat without filtration; shooting into the sun, even a setting one, creates myriad exposure problems for a camera – be it of the point-and-shoot, APS-C or Full Frame sensor variety. Therefore I used a HARD GND8 to bring down the light in the sky and fired away.

How did I know I should use a GND8 and not a GND2 or GND4? Experience, really. I’ve shot a lot with filters over the last two years and I’ve come to know what to expect from them under certain conditions. You could, of course, meter each part of your scene individually with your cameras spot meter – the setting sun and then your foreground element – to learn exactly what filtration to put on the lens, but you might miss the moment. I prefer to rely on instinct and the feel of the scene, for better or for worse (I’m not sure if Thom would approve of this run-and-gun approach!).

Technical considerations.

Never purchase a circular GND filter. They are useless. Thom Hogan agrees with me on this. A circular GND places the transition line in the center of your image, the last place you really would want to use it. Your best bet is to go with a rectangular system. If you’re

Above is another example of how to use a GND. The filter I used here has a value of 4. I twisted my filter holder (more to come on that!) as to line up the vanishing point of the sand dunes with the hard edge of the GND. Shooting away from the sun and still early in the morning I didn’t need quite as much filtration to get my sky where I wanted it to be. In addition, to increase contrast and saturation in the scene, I used a Circular Polarizer.

Above is another example of how to use a GND. The filter I used here has a value of 4. I twisted my filter holder (more to come on that!) as to line up the vanishing point of the sand dunes with the hard edge of the GND. Shooting away from the sun and still early in the morning I didn’t need quite as much filtration to get my sky where I wanted it to be. In addition, to increase contrast and saturation in the scene, I used a Circular Polarizer.

PART 2: CIRCULAR POLARIZERS (CP-L)

I could have started with the CP-L as it is the one filter everyone needs to have in their kit. A CP-L is useful when you want to alter elements of a scene. You can use them to cut down on reflections in water (it does this by altering the way certain waves of light hit the glass and thus your sensor/film). You can use them to cut down on reflections when shooting through glass, if you are shooting a particularly interesting mannequin through a storefront window, for example (heh). You can use them to cut out reflections in foliage thereby increasing saturation and contrast throughout your scene. You can also use them to increase saturation and contrast in a bright sky, as most people have been doing with their CP-L filters since time immemorial. When I’m on the road and I know my day will include a lot of outdoor shooting in a variety of locations I will often have a high-quality CP-L on my wide to medium-angle lenses. Let’s work through some examples.

Above is an image made at Mui Ne Harbour in Vietnam. This image was made late in the day – you can see how long and low the shadows are coming off the boat – but I still needed a little help getting the right amount of colour and saturation out of the sky. With a CP-L on the lens, twisted into the correct position, reflections in the water are minimized (giving it a richer tone) and the sky is darkened nearly a stop. This image wouldn’t have nearly as much character if I had not used a CP-L.

Above is an image made at Mui Ne Harbour in Vietnam. This image was made late in the day – you can see how long and low the shadows are coming off the boat – but I still needed a little help getting the right amount of colour and saturation out of the sky. With a CP-L on the lens, twisted into the correct position, reflections in the water are minimized (giving it a richer tone) and the sky is darkened nearly a stop. This image wouldn’t have nearly as much character if I had not used a CP-L.

Above; an image of sand dunes near Mui Ne, southern Vietnam. The effect of the CP-L is very pronounced in this black & white treatment. With the light low and soft at the end of the day and shooting away from the sun there was no need for a GND in this scene, but I did want to darken that sky just a little bit and I did that by cranking my CP-L around. The CP-L,in addition to being the most useful of all filters, is also the most versatile and easiest to use.

WARNING!

Be careful how you use a CP-L on ultra-wide angle lenses (anything wider than 16mm, specifically). Because the field of view is so wide your CP-L can actually discolour parts of your landscape, not only your sky. Users of the Tokina 11-16mm f/2.8 (which I am one), Sigma 8-16mm, Canon and Nikon 10-24, etc. need to be very careful of this. When using an ultra-wide angle lens you also need to make sure you purchase a slim-profile CP-L to ensure that it does not vignette; if you’re cropping in from 10mm on all your photos in post production you are defeating the purpose of using an ultra-wide in the first place.

More from Thom Hogan on the polarizer:

- Pros: give you control over reflections; tend to increase contrast and color saturation; can be used to darken bright skies

- Cons: relatively expensive for a good filter that won’t vignette on wider lenses; polarization effect will vary across scene with wide angle lenses; some multi-part polarizers are prone to fogging; effect can’t always be maximized (Hogan, 2003).

Part 3: Neutral Density Filters (ND)

Above; a Neutral Density filter with a value of 4.

It may seem as though I am running out of order in this guide, introducing the ND after the GND, but there is a method to this madness. I’m discussing the ND here because it is a filter I use less often than either the GND or the ND. ND filters are also more difficult to use well. Before we discuss uses, lets discuss the facts. What is a ND filter?

A ND filter is a chunk of glass that blocks a certain amount of light from entering your lens and therefore striking your sensor or film. It’s as simple as that. A good ND (re: high quality) is of totally neutral colour and will not cause colour shifts (cheap ND filters notoriously shift magenta). Like GND filters, ND filters come in grades of 2, 4, 8 and even 400 and 1000. We’ll start with the little guys and work our way up.

What do I use the ND filter for?

* Slowing shutter speed

* Getting into a workable flash sync zone (my favourite!)

* Using large aperture lenses in bright light

I started experimenting with ND filters because I wanted to create interesting effects with water. I wanted to create glassy, smooth surfaces. In the image above, shot over the Han River in Seoul, Korea, I was able to smooth our the rough surface of the water using a ND8 filter. This gave me a 1 minute exposure with an aperture value of f/32 and an ISO of 100; right at the limit of what this lens and camera combo were able to handle. However, with the water being rough as it was, it didn’t need much more than 1 second to smooth out for me. I used the Cokin P System and the aforementioned ND8 to create this image.

I started experimenting with ND filters because I wanted to create interesting effects with water. I wanted to create glassy, smooth surfaces. In the image above, shot over the Han River in Seoul, Korea, I was able to smooth our the rough surface of the water using a ND8 filter. This gave me a 1 minute exposure with an aperture value of f/32 and an ISO of 100; right at the limit of what this lens and camera combo were able to handle. However, with the water being rough as it was, it didn’t need much more than 1 second to smooth out for me. I used the Cokin P System and the aforementioned ND8 to create this image.

Technical Considerations:

Buying cheap ND filters (the Cokin P system, while pretty versatile, is still cheap) is often a trade off. Of course, they are cheap. So that’s a positive. The average Cokin P filter runs about $20 USD. They are not, however, totally neutral in tone. Often I would see a magenta cast to my images when using a single Cokin ND. When I stacked them, as I did before I bought heavier filtration, I always saw the colour shift. See below for a prime example.

Above; not a good image by any stretch of the imagination, but a prime example of what you can expect if you decide to stack low-quality ND filters on top of one another. Here I’m stacking two GND8 Cokin P filters to allow me to slow my shutter speed enough to smooth out the water. This image is straight out of camera. It’s not pretty. If you intend to convert to B&W later (like I did with my shot of the bridge) then this obviously won’t be a problem for you, but for those of us who want to shoot in colour and like to make long exposures in daylight a better filtration system is the answer.

Above; not a good image by any stretch of the imagination, but a prime example of what you can expect if you decide to stack low-quality ND filters on top of one another. Here I’m stacking two GND8 Cokin P filters to allow me to slow my shutter speed enough to smooth out the water. This image is straight out of camera. It’s not pretty. If you intend to convert to B&W later (like I did with my shot of the bridge) then this obviously won’t be a problem for you, but for those of us who want to shoot in colour and like to make long exposures in daylight a better filtration system is the answer.

Above; another example of how and when to use a ND filter. This image of a speeding train at Osan College Station in Osan, Korea was made with a Cokin P ND4 (it was later in the day and I didn’t need nearly as much filtration as I would under direct sunlight). A 1 second exposure, aperture value of f/11 (with an APS-C sensor it’s much better to shoot between f/11 and f/16 to avoid sharpness-robbing defraction) and ISO 200. Using ND filters are a great way to communication speed and motion through blur.

Above; a Cokin P ND2 in action. I’m using the filter here to allow me to create contrails out of the speeding vehicles. Images like this aren’t nearly as impactful if they include a bunch of frozen cars and trucks.

When scenes are exceptionally bright yet you still want to slow your shutter speed you need heavy-duty filtration. I swear by the ND1000 – the granddaddy of all filters. Using a ND1000 is difficult and time consuming; because the filter is so dark it’s nearly impossible to compose images with it on the end of your lens. Instead, you need to composure your image with your camera on a tripod, screw your ND1000 onto the end of your lens when you’re ready and do your best to estimate a proper exposure (you could of course do the calculations manually… but there’s no fun in that). When using a ND1000 (or ND400) you must make sure to lock your lens into manual focus mode; with the filter being so dark the lens will hunt back and forth for focus for a moment before just giving up. In the above image, made on Koh Samui, Thailand, I used a ND1000 filter to smooth out the ocean. The waves weren’t particularly rough so I needed as much time as possible to smooth things out to this degree. Even with the ND doing the dirty work at around 10 stops of light blocking ability I was only able to pull off a 46 second exposure at an aperture of f/22 at ISO 100. Obviously I couldn’t have got anywhere close to that with a GND8 or a pile of them stacked on top of one another.

NEXT: Getting into a workable flash sync zone (my favourite!)

From Thom Hogan:

Obtaining flash sync speeds. In bright light with cameras that have slow flash sync speeds, you might not be able to use flash without an ND filter, because you can’t set an aperture/shutter speed combination that falls within that allowed by the camera (Hogan, 2003).

He’s right on the money here. I do a lot of Flash shooting, in case you didn’t know, and the ND filter is often my best friend, especially when shooting outdoors. My go to camera these past couple of years has been the Nikon D90. It has a max sync speed of 1/200 of a second; this means that I need to keep the shutter at 1/200 of a second or slower in order to use flash (we will NOT get into high-speed sync at this moment, thank you very much!). What does that mean in practice? Take this scenario:

I’m on assignment shooting a musician for a magazine in Seoul, Korea. The plan is to shoot this musician in the street, in a highly populated area, at or around dusk. I plan on shooting into the sun, too, so it will act as a back/rim light and really make the image pop. The problem here is that in order to bring down the ambient light in the scene – the sunshine – I need to use a fast shutter speed. At an aperture value of say, f/9, that likely means a shutter speed of approx. 1/500. Too fast to use flash. However, since we know a little about using ND filters now we know exactly how to solve this problem. We slap one onto the front of the lens – a ND4, in this case – and fire away at a healthy shutter speed of 1/200 and ISO of 125.

Above; the case study in completion. Greg James Hanford, rockstar, and some fantastic members of the Seoul Photo Club, working hard. The ND filter is really worth its weight in gold when it comes to getting yourself into a workable flash sync zone. Without a bag of these little guys I wouldn’t be able to do half of the outdoor shooting I do.

Above; a much more subtle use of the ND. Here, shooting DJ Ross McKay, I utilized a ND8 filter to give me a shutter speed of 1/4 of a sec – just long enough to blur the people walking by in the background – and a flash unit in a small softbox on Ross to keep him crisp. There are endless ways to use ND and flashes together in the field and I’ve only briefly touched on these here. In a coming appendix to this post I’ll be working through advanced flash & filter techniques for those who want to see what these things can really do.

NEXT: Using large aperture lenses in bright light

I won’t spend a lot of time on this section as by now the headline should explain exactly what I’m talking about. ND filters are great if you’re the type of shooter that wants to shoot wide open, day and night. If you’re using lenses in the f/1.2 – f/1.8 range and you like to shoot those expensive pieces of glass wide open then you will often encounter times when you need a little ND action to block some light from hitting your sensor. Of course, if you’re the type that has a f/1.2 lens you are well aware of this already and this point is moot. Once more, if you’re the type that has a f/1.2 lens you’re probably thinking I’m insane for suggesting you slap a piece of low-grade glass in front of it to block anything, but what do I know. I do it.

Part 4: CREATIVE FILTERS

Serious photographers would never consider gimmicks like coloured filters, would they? Sure they would. they do it all the time. And why not? It’s just one more way of experimenting with your photography. Now, I’m not advocating you use a bunch of rainbow, starburst or double exposure filters – those are just silly – but there are times I like to use creative coloured filters to spice up an image. I use two – and only two – and I use them sparingly. The one I use most often and for the most dramatic effect is my cokin tobacco filter.

Anyone that has been following my work for any length of time has probably seen this image somewhere. It is a classic example of how to use a creative filter effectively. I places the transition line of the filter (where it goes from clear to coloured) directly along the line of the pond in front of Angkor Wat and let the filter do the rest. I use this filter to enhance what’s already there in the sky. If there are reds or oranges (as there were on this day) then I fire away. I use it as sparingly as possibly and never force the issue; using coloured filters when there’s no need or when they really stand out is the surest way to creating cheesy images. Of course, this is all to taste, but after experimenting with these filters for a little while you’ll see exactly what I mean.

Above; using a creative coloured filter for dramatic effect one more time. Once again I’m using the Cokin Tobacco filter to intensify the bright oranges and reds in the sky. At Angkor Wat it was sunrise; this time, sunset. I places the transition line at or just above the horizon and composed the image like I normally would. One thing to keep in mind is that the tobacco filter blocks a lot of light from passing through above the transition line, so you generally need to use it in situations like this, when you’re dealing a scene that has extreme variations in exposure levels.

Above; using a creative coloured filter for dramatic effect one more time. Once again I’m using the Cokin Tobacco filter to intensify the bright oranges and reds in the sky. At Angkor Wat it was sunrise; this time, sunset. I places the transition line at or just above the horizon and composed the image like I normally would. One thing to keep in mind is that the tobacco filter blocks a lot of light from passing through above the transition line, so you generally need to use it in situations like this, when you’re dealing a scene that has extreme variations in exposure levels.

PART 5: STACKING FILTERS FOR DRAMATIC EFFECT

I break the rules all the time. Any photographer with half a brain knows that you don’t stack filters. Stacking filters leads to a degradation of image quality (defraction, glare, flares, sun spots, bursts, etc). Stacking filters leads to a dependence on filters. Stacking filters is bad.

Most of the time I agree with this. However, from time to time, I like to shake things up a little. Yet I never stack filters for the sake of stacking them (like I’ve learned not to use ten flashes just for the sake of using ten flashes). There has to be a rhyme and reason to using so much excess glass in an image. Image quality should be and always is of utmost concern but every now and then you can bypass the rules and come out the other end looking like a champion. I’ll examine a couple of cases here.

When I first posted the above image to flickr I wrote this under GEEK:

– Cokin Tobacco Filter to deepen sky colour

– Circular Polarizer to flatten reflections

– Graduated ND8 filter to bring down the brightness in the sky

Could I have got away with a single filter in this scene? Could I have used one polarizer or one GND or one creative filter? Not very likely, not without bracketing and then combining photos later in photoshop (and who wants to spend the time doing that?) I strive, when and where I can, to create my effects in camera and to realize my vision for this image I had to stack filters one on top of the other. You can see, even after all those layers of glass in front of my lens, the sun is still pretty bright. Let’s look at another example.

This is a water mosque on an island near Malaka, Malaysia. I’m shooting this just as the sun is going down so the disparity between sky and water isn’t all that great. In this first image I’m using only my CP-L (being careful when doing so with the wide-angle lens, of course!). As you can see, this image is a little flat straight out of camera as it is. It’s a fairly accurate representation of the scene as it was (save for a weird White Balance issue that I would normally solve myself in post-production). Thinking on the fly and wondering what I could do to make this image really pop I went into my filter bag for help.

As you can easily see I’m using the tobacco filter here, but mostly as an example and a warning; as I’ve stated previously, use this thing sparingly. It simply doesn’t work here and makes the entire scene look goofy. The sky simply isn’t believable. I see far too many images created like this, photographers forcing filters into a scene that they flat out have no business being in. It’s ugly. It’s weird. It’s an experiment. Try it… just don’t ever share it with anyone (no, really).

On to the next one. Above; an image created with a plethora of filters. I’ve been asked about this one a few times so I thought I’d share the specifics, despite having listed the information in the original post on flickr.

Geek:

CP-L to flatten reflections on the water

Graduated ND8 to bring down the bright sky

Graduated Sky Blue filter… for fun

ND1000 to smooth out the water

I started with the ND1000 on the lens to give me a long exposure and not force in into tiny aperture range; I wanted to shoot this around f/11 and not f/32, like I had to shoot the first of these three images at. Then, with my Cokin filter holder attached to the ND1000, I dropped in the cokin CP-L (I don’t use this as often as I use a screw in CP-L, but I needed to here). The I added a GND8 to soften the light and finally a Graduated Sky Blue filter for a little colour pop. This last one you could add in post-production easily enough, but as I have stated I like to do most things in camera. Technical details for the image include; f/16, ISO 100, 13 sec. exposure and a focal length of 14mm. In post I did a little dodging and burning to the mosque itself and added a vignette but otherwise tried to do as much work in camera as possible. It might look complicated, but it’s not.

And there we have it, folks. The first edition of my filter guide. I’ll look to update this more and more if anyone expresses interest, though an expanded edition will debut with my Light Guide to Asia due sometime in January.

Thanks for dropping in.

Great post matey – and just in time for me to really get the most out of the ND stuff you recommended on an upcoming trip to Thailand! ha!

One quick question, if you’d be so kind…

You say “With a CP-L on the lens, twisted into the correct position, reflections in the water are minimized (giving it a richer tone) and the sky is darkened nearly a stop.”

Erm… how do you twist a CP-L into the correct position?? Do you have some mysterious graduated version?? All the CP-L filters I’ve seen (or purchased) are a solid colour… I never realised there was a graduation or adjustment element to them…

Jay, are you sure you’re not thinking of an ND filter rather than a CPL?

All Circular Polarizers have a ring that allows the user to twist the glass in a way that will position it as to cut down reflections, etc. In effect, yes…. they are all graduated. Not just mine. You can see this by simply holding the CPL up and twisting it in your hands. That’s dumbing it down, though. Check out this article: It’s excellent and discusses both circular and linear polarization. Must know kind of stuff for outdoor photography.

The reason a CPL has a ring that allows you to twist the element is that you don’t always shoot in one orientation. Sometimes you shoot in landscape, sometimes you shoot in portrait. When you alter the angle of your camera you need to be able to twist to CPL to manipulate the wavelengths of light attacking it. But I digree… read this article, it’s great. And have fun in Thailand!

http://www.bobatkins.com/photography/technical/polarizers.html

Pingback: What’s Up Ahead « Hermit Hideaways

Pingback: Filters & Upcoming Content « Hermit Hideaways

Pingback: Neutral Density Filters « WelkinLight Photography

how are you I was fortunate to search your theme in yahoo

your topic is brilliant

I learn a lot in your topic really thank your very much

btw the theme of you blog is really wonderful

where can find it

Pingback: Take Better Pictures: 5 Korean Photo Blogs You Should Follow : The Nomad Within

Pingback: 12 Photos | A Travel Essay: Sumatra & Java, Indonesia : The Nomad Within

I just read this for a second time a few months later and it’s much more clear to me now that I’ve had my camera for a few months. I was out with my 35 1.8 on a very bright day, shooting wide open and was frustrated I couldn’t get my shutter speed high enough. Sounds like I just need a ND filter.

That’d help for sure! You can also try lowering your ISO before you add a filter

Mate – just wanted to say thanks again – this post REALLY helped me get my head around the how, but more inportantly, the WHEN of filters…

Which allowed me to get this shot – I like to call it my “Flash Homage” hhahha

Thanks again buddy – also – when the hell are you in Seoul again?? I feel like I owe you a beer! ha!

Pingback: 12 Photos | A Travel Essay: Sumatra & Java, Indonesia : Korea How

Thanks for this… very, very helpful.

thanks for checking it out, Adam! Glad I could help.

Pingback: Korean Photography Blog » UV and Polarizing Filters: The Two Filters You Should Have in Your Bag

Hey Shawn,

So, I have Cokin P System gear and make use of the GND 8 most often. However, I often get gnarly lens flares when shooting into the sun that are anything but aesthetically pleasing. I recently posted a photo to Flickr wherein I was making use of the sun peeking in over some buildings to get a sunsatar, while using the GND 8 to keep the sky from being a blown-out mess. Because of that, I got some green, hazy flares, a small, fuzzy spectrum flare, and a couple of red dots. Thankfully, I have pretty good command of Photoshop and was able to clone over or otherwise reduce the flare problem – still, I’d rather not do that. Is this a common problem, as I assume it is? And regardless, will/should I simply continue to fall back on my Photoshopping abilities, or do something differently when I want/need to shoot into a bright light source?

Tony –

Short answer; yes, it’s a common problem. It’s a common problem whenever you put an extra piece of glass in front of your lens and try and shoot into the sun or have light coming in at awkward angles. In this case it has less to do with the grade or make of the filters and more to do with the physics of light. You could cut down on a LITTLE of that using the Lee resin or Lee glass filters, but you’re still going to get these problems. The only thing you can really do is watch your angles when shooting into bright light. I come across this problem all the time and when I do I eschew filters altogether. When I can’t get what I want in a single frame with filters and the flares, dots, etc. are too much I will bracket 3-7 images then fuse the exposures in post. I stay away from this as much as I can as I like to do everything in camera, but sometimes it’s the difference between a clean image or a spotty one. That’s probably my best advice for this scenario. Besides, shooting into the sun you’re going to need heavy, heavy filtration anyway and one grad often isn’t going to be enough. Even when shooting with a simple polarizer into the sun things can get messy. When you start stacking 1×1 filters it’s really often troublesome.

Cheers, partner. I hope that answers at least part of your question!

Sure does, Shawn. That’s basically what I figured, but I wanted to check with the master. I also tend to avoid bracketing and merging, but that’s only because I’ve never done it enough to know what I’m doing there. I should try it more often.

Thank you very kamsa! Great post!

Agreed – I avoid it, but it does have a place in the bag of tricks. Glad this has been helpful, I need to refine it a little more, me thinks!

Pingback: Jason Teale's Photography Blog » UV and Polarizing Filters: 2 Filter’s you should have in your Bag

Pingback: Dongdaemun History & Culture Park at Night / Photo & Travel Links: May 28, 2011

Pingback: Dongdaemun History and Culture Park | Nanoomi.net

Pingback: Improving your pictures – The Overview « WelkinLight Photography

Pingback: Improving your pictures – The Overview | Flash Light Photography Expeditions

Pingback: From the rooftops

Pingback: Go-To Guys